When the Centre Cannot Hold: Leadership in Times of Unraveling

.

Turning up when the sun shines and Ted, the dog, needs walking is a tightrope kind of privilege that feels at odds with witnessing the massacre of an entire people, and knowing that in many other parts, the sun burns through the skin of both earth and humans. And here I am, trying to stay centered and focused and not let it all fall apart—for what good would that do?—when I could be doing something useful? Or not...

I know that there is a time for holding the line (the dog needs to be walked before the heat sets in), and letting the threads of the everyday unravel is to be within the gnawing discomfort of bearing witness. But even that feels like an academicized hollow gesture that keeps me intact, when the horror of letting it all fall apart might only be wallowing in my own inadequacy. Yeats puts it well:

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

— The Second Coming, W.B. Yeats

The innocence of denial is drowned for sure. I cannot be the only one thrashing around in search of a thread through. Yet it rarely enters my coaching work with leaders unless gently invited. The urgency to take action is palpable, but no one draws breath for long enough or mentions the falling-apartness of it all.

We are still attached to models of innovation that disguise a tendency towards competitive do-or-die growth.

Pat wants his model of the world reflected in how his team implements a new reporting system. He believes it will lead to more funding from a shrinking government pot, but he doesn't see how the prospect of success is dreaded by some project team members who are struggling to cope with the day-to-day grind. They serve a community-based client group just that bit less able to hold their lives together than the staff are. He wonders why they just don't get it and fill in the forms. The more he meets, the more time he spends picking up on more things left undone, until one day his strongest ally ups and leaves. And the battle continues until he admits he is at a loss. He does not know how to go on: the small world that is his domain sits within a larger world of infinite decline, and the exceptionalist stance that "this work is too important" has been breached.

He, like me, has no choice now except to "get over ourselves." Amarantho Robey offers a really important insight into leading by becoming the eye of the storm rather than trying to control it. He writes about shifting from reactive control to creative leadership (https://lnkd.in/eWXTrbwf.).

For me, this starts with becoming aware that we are, in the words of Kathia Castro Laszlo, #systems beings—recognizing that getting over ourselves is "an inside job, a learning journey" that embodies an expanded sense of self and knowing that there is no exceptionalism when it comes to our shared humanity, and the animals and plants with whom we share this living earth. And taking it from there.

There were a couple of things we learned about Ted when we let go of the leash and stopped roaring after him until he had gone far enough to ensure we were still in view: when he swims after ducks, they fly off. When met with waves, he jumps over them. And when he runs downstream and finds his return involves a steep ledge, he can do parkour. That, in the words of Amarantho, is to unleash potential.

Developing a Systems Thinking Lens for Collective Leadership

We can let change just happen or we can be purposeful about creating the changes we seek. In order to understand what is required, it is necessary to understand the challenges that complex problems pose and how they manifest in the situation you are looking at systems thinking for leading in times of uncertainty — on issues big or small

Cover: Developing a Systems Thinking Lens for Collective Leadership, written by Joan O’Donnell for Collective Leadership for Scotland, Scottish Government

There is a growing realisation that traditional policy-making processes struggle to be effective in a world where issues cannot be contained by national boundaries or different administrations, and where linear cause-and-effect relationships no longer apply. Blueprint planning and log frames might get us from A to B on a long journey: indeed, it served public services well when operating environments were complicated but considered stable. It is less useful for the complexity and uncertainty we are now operating within, however, where the speed of change is faster than any generation has experienced before.

Responding to complexity involves understanding that different kinds of problems need different kinds of responses. In other words, the tool must fit the job in hand. Complex situations have no natural boundaries such as child poverty or climate change and are characterised by interdependencies, multiple stakeholders, and unknown boundaries -and while cause and effect are still linked, the consequences of any one intervention cannot be determined in advance. They are subject to emergence.

This guide, developed for the Collective Leadership for Scotland unit within the Scottish Government acts as an easy-to-read guide to support you to begin a systemic inquiry into a situation that is of concern for you. Note that you might have a situation that is concerning you that concerns an immediate situation in your own home or community or on a grand scale in public sector governance. It doesn’t matter what the size of the situation is, this guide offers some support for beginning the process of working through the situation in a systemic way, without having to go deep into the myriad of methodologies out there that support systemic change.

It is grounded in an understanding that you need to consider the interrelationships between different problems, and acknowledge and work with differences in opinion of what the problem is and what you should do about it. It also encourages you to think critically about what you are including and excluding in the boundary you draw around the problem.

And of course, it may prompt you to delve deeper into how to be more systemic in your work or home or policy design….

O’Donnell, Joan (2023): Developing a Systems Thinking Lens for Collective Leadership. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22241143.v1

Systems Thinking in Research: Considering Interrelationships in Research Through Rich Pictures

Bob Williams, Joan O’Donnell

The third of a series of blogs on using systems thinking in doctoral research that were originally published on the ALL Institute Blog, Maynooth University based on training provided to ADVANCE CRT PhD students..

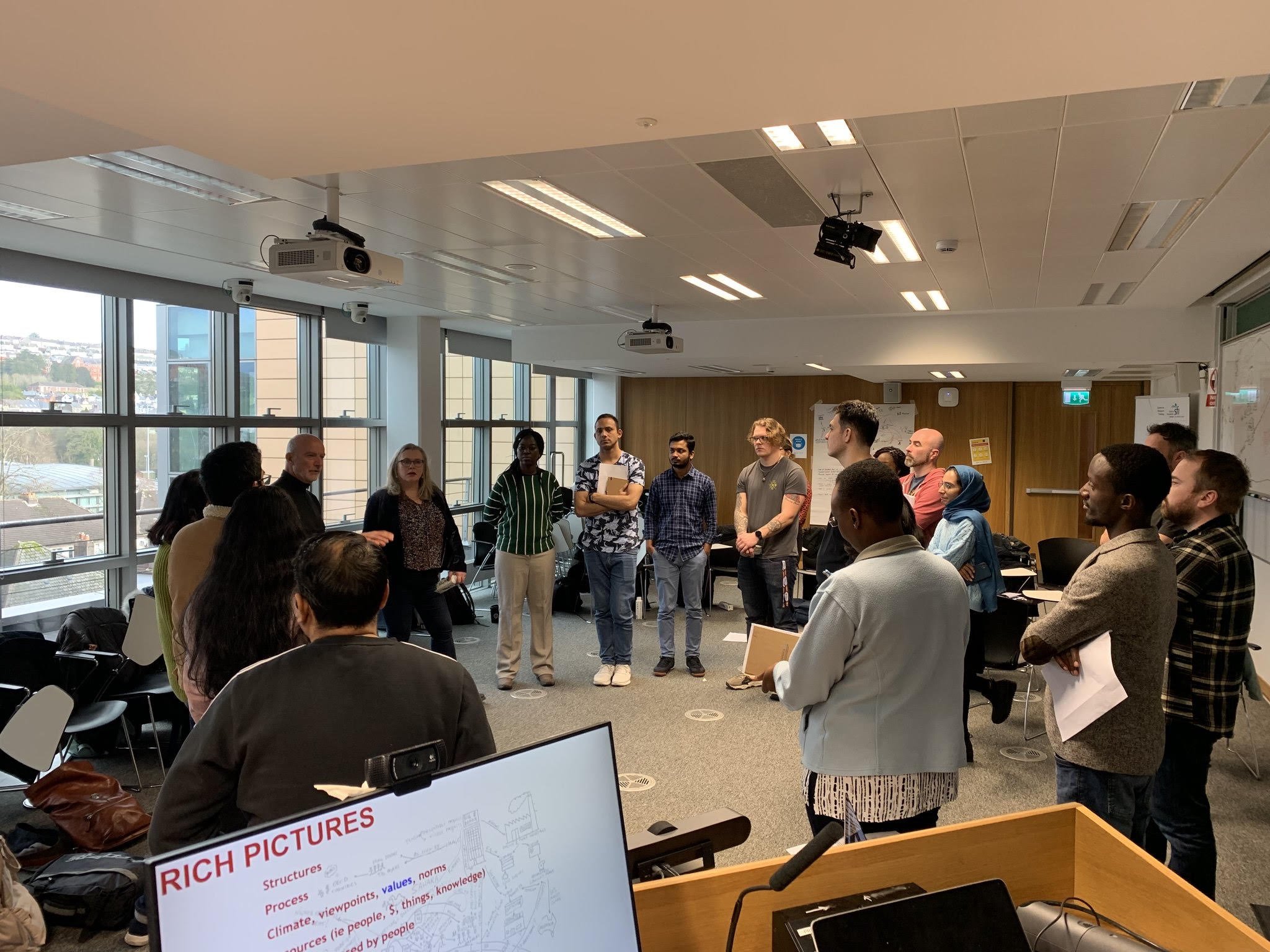

Bob and Joan with 1st year ADVANCE CRT Student Induction, Cork, Ireland January 2023

Let’s start with a true story. It follows on from our last blog about focus and scope. But it highlights our tendency to start with focusing in on the subject of our research — with boundary setting — rather than considering the wider scope, especially when faced with ‘a problem’ that we hope our research will address. Stating that something is a ‘problem’ is a form of boundary setting, as we will see.

Some years ago, Russ Ackoff, a leading systems thinker, was approached by a major machine tool manufacturer experiencing considerable fluctuations in demand for its products. This created problems of low morale, poor productivity and bad industrial relations. Russ was called in to sort out this issue which was framed by the company as a ‘production smoothing’ problem. The organisation’s senior management asked Russ to work out how it could smooth out its production so that it can avoid negotiating layoffs and then running around trying to recruit people some months later. After a considerable amount of investigation, Russ told them that they would never find a solution if they continued to see (i.e., frame or bound) the problem in terms of production smoothing.

However, he said, there may be a solution if the company framed the problem as a demand smoothing problem. To smooth demand, you needed to find a product that was counter-cyclical to the demand for the company’s existing product line. After much research, the company found that, not only was the demand for road-building equipment counter-cyclical to that for machine tools, it also required much of the same technology, labour skill-set, marketing and distribution as for manufacturing machine tools. The company accepted Russ’ recommendation and started manufacturing road-building equipment. This stabilised production and labour; it also considerably increased the company’s profit margins. Indeed, these days the company is better known for its road-building equipment than its other products.

How many times have you rushed, like managers at that company, into identifying ‘a problem’? Why not stand back, a bit like Russ suggested, and consider whether that really is the right way of responding to the situation that, for you, is problematic. Notice the difference in language. In systems language, a problematic situation is a situation that concerns or interests you for some reason. But that situation may contain many different ‘problems’; your initial choice of ‘the problem’ (a boundary choice) may not be the most appropriate focus for addressing the situation that concerns you.

So, what does systems thinking have to do with this issue?

Recall the diagram below from our previous blog:

Distinguishing between focus and scope in research

Even in a PhD you often start with focus on, for example, the key topic of your PhD project. But that already contains a series of boundary choices that provide the ‘lens’ through which you understand and subsequently explore the scope of your PhD. That company’s focus on ‘production’ led them to see and explore the scope of the issue only in ‘production’ terms. And that would prove to be unhelpful. It was only when it changed its focus to ‘demand’ could it then view the scope of the situation in ways that would lead to a solution. But it didn’t just pick the new focus at random. The new focus emerged by stepping back from the original focus and exploring a broader scope, inter-relationships and perspectives, that ultimately allowed Caterpillar to identify and narrow down on a more useful focus. Having done this, they were then able to cycle again around inter-relationships and perspectives to arrive at a particular solution, and in doing so they worked out what was feasible and desirable to do, to systemically address the problematic situation.

PhD Students from ADVANCE CRT Student Induction, Cork January 2023

So where do you start when exploring the scope for your research? Do you start at inter-relationships or do you start at perspectives? Do you start with ‘reality’ or people’s perceptions of ‘reality’? You will notice on the triangle diagram that the arrows go both ways, so, as long as you understand that the two are linked then it really doesn’t matter which you start with.

In this blog series, we will start with understanding inter-relationships and then move to engaging with the multiple perspectives that people have of reality.

So, what are the kinds of questions that a systemic inquiry into your research situation pose? Here are some examples:

What purposes does your research situation appear to be fulfilling?

Whose or what needs are and are not being addressed from your research?

How do the current and past actions address these needs (if at all)?

Which parts of your research situation have too many things to cope with compared with their ability to respond? How does that affect one’s ability to address the needs and achieve the benefits and purposes?

How does the information necessary to fulfil those needs flow around your research situation?

In what ways are the rules (what must be done), roles (who does what) and tools (things you use to do it – including language) operating within your research situation influencing the ability to fulfil those needs?

How do the tasks you have to do, the way your work is coordinated with others’ tasks, the overall management of your PhD, its responsiveness to things relevant things outside your PhD, work together?

What kind of puzzles and contradictions are there within your research? What are the consequences for whom?

How significant is the difference between what you feel you ought to do and what you are able to do? How can you manage that?

That’s a lot of complicated questions and there are many ways in which the systems field explores them. Diagrams are frequently used to do this. There are, of course, many kinds of diagrams. One that is especially good at exploring a complex situation is Rich Picturing.

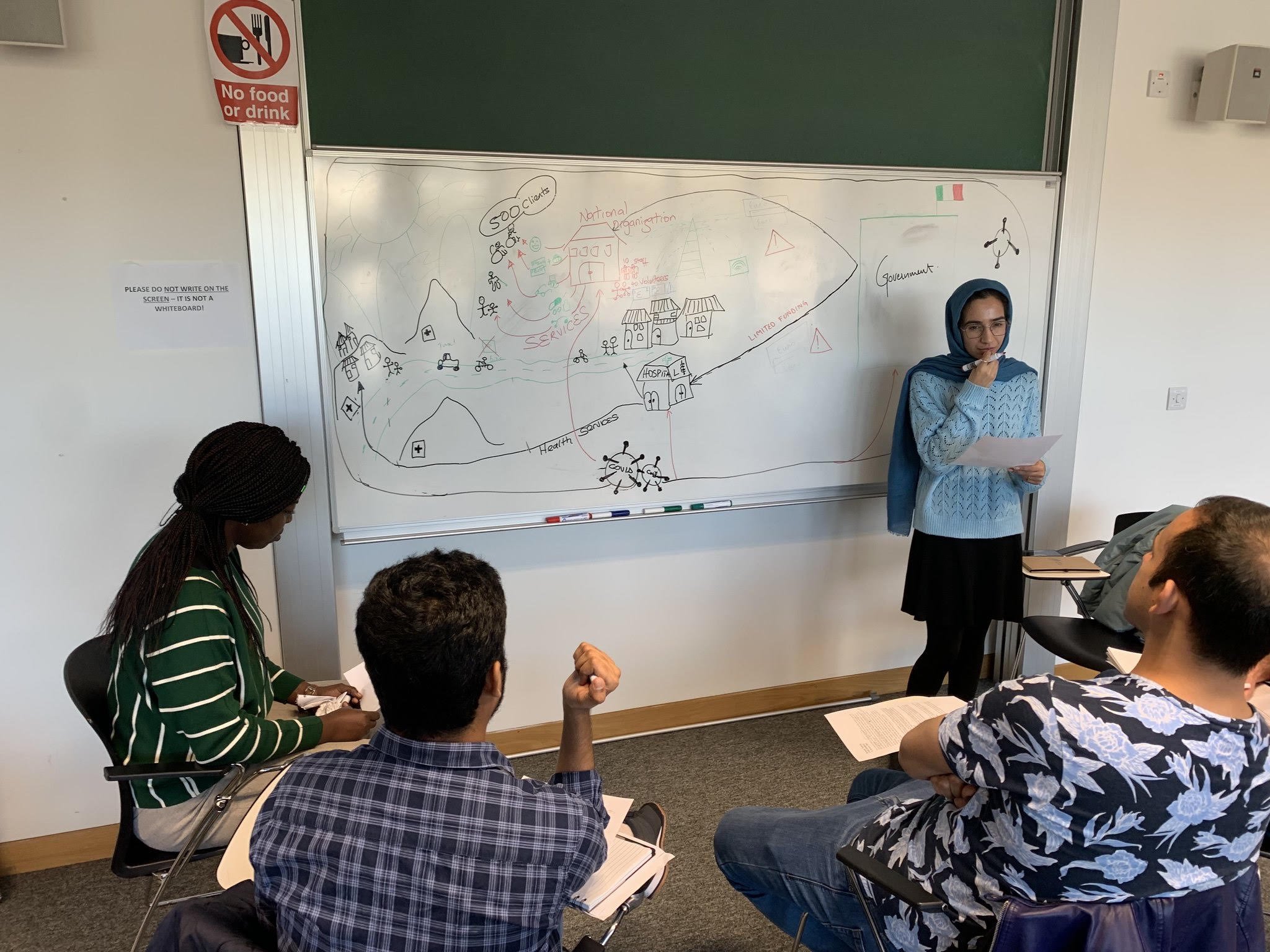

Rich Pictures

Rich Pictures are part of a systems methodology called Soft Systems Methodology. A Rich Picture intends to visually represent as many of the following aspects of the situation of interest as possible:

What purposes does your research situation appear to be fulfilling?

Whose or what needs are and are not being addressed from your research?

How do the current and past actions address these needs (if at all)?

Which parts of your research situation have too many things to cope with compared with their ability to respond? How does that affect one’s ability to address the needs and achieve the benefits and purposes?

How does the information necessary to fulfil those needs flow around your research situation?

In what ways are the rules (what must be done), roles (who does what) and tools (things you use to do it — including language) operating within your research situation influencing the ability to fulfil those needs?

How do the tasks you have to do, the way your work is coordinated with others’ tasks, the overall management of your PhD, its responsiveness to things relevant things outside your PhD, work together?

What kind of puzzles and contradictions are there within your research? What are the consequences for whom?

How significant is the difference between what you feel you ought to do and what you are able to do? How can you manage that?

That’s a lot of complicated questions and there are many ways in which the systems field explores them. Diagrams are frequently used to do this. There are, of course, many kinds of diagrams. One that is especially good at exploring a complex situation is Rich Picturing.

Rich Pictures are part of a systems methodology called Soft Systems Methodology. A Rich Picture intends to visually represent as many of the following aspects of the situation of interest as possible:

The structure of the situation;

The processes between elements of that structure;

Important aspects of the situation that affect how the stakeholders, stakes, structures and processes interact;

The nature of the interrelationships (e.g., strong, weak, fast, slow, conflicted, collaborative, direct, indirect);

Purposes, aspirations, and goals;

Motivations;

Values and norms;

Environmental aspects, e.g., a climate of opinion;

Issues, conflicts, and agreements;

Resources (e.g., people, money, tools, skills);

Importantly, they need to illustrate things you don’t know or puzzle you. After all, why would you be doing research if you already knew the problem and solution.

Here is an example of a Rich Picture. It illustrates a problematic situation around rice production in Mali.

Rich Picture of a problematic situation related to rice production in the Sahel region of Mali (Bob Williams)

You will see that it is a mixture of pictures and text. This is deliberate. Sometimes, a picture tells a 1000 words – it is a shorthand that makes it possible for you to explore the entire scope of your work at a single glance.

Rich Pictures are often drawn before you know clearly which parts of a situation you should be focusing on. It is that ‘standing back’ phase, which helped Russ Ackoff change the framing of ‘the problem”. Therefore, when drawing a Rich Picture, free your mind as much as possible from any preconceived ideas you may have about the situation. People drawing Rich Pictures for the first time often try to place too much order too quickly into a situation. The drawing reflects any chaotic mess of thoughts and perceptions that pours down your arm from your brain, out of the pen in your hand and onto whatever surface you are using to draw the Rich Pictures. They can get very messy indeed, but often the messiest pictures are the richest and most meaningful.

Whatever it looks like, it is very important that the Rich Picture conveys all the important elements of a situation (see the above list) without overly imposing your own understandings and prejudices. In Rich Picturing, you are drawing the unstructured messiness of the problem that will allow you to think systemically about that situation.

Thus, Rich Pictures are a means for moving from a state of messy confusion, where all you know is that you’re dealing with a problematic situation, to a state where you’ve identified one or more potential foci that you want to address. But, before you finalise that, you need to explore the matter of how different people will interpret your Rich Picture and consider what that implies for your research focus. One approach is to bring other people into the Rich Picturing process to provide their own knowledge and perspective. This can be either your supervisor or other stakeholders directly involved in, or affected by, the situation. And that brings us to consider the value of exploring multiple perspectives that will ultimately help you decide your research focus.

This article was first published by the ALL Institute and has emanated from research supported in part by a Grant from Science Foundation Ireland under Grant number 18/CRT/6222. The opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Science Foundation Ireland.

For further information, you can contact Bob: bob@bobwilliams.co.nz or Joan: joan@systemsbeing.com.

Getting to the heart of designing research using systems thinking

Bob Williams, Joan O’Donnell

The second in a series of blogs based on designing systemically informed research

Joan and Bob (who has monkeys on his head)

Nobody would deny that research is a complex business. One of the most complex decisions is deciding the focus of your research among the vast range of possibilities that lie within its scope. This blog explores how understanding and addressing three different kinds of complexity can help with that tricky decision. Ontological complexity helps you address the reality you are dealing with; cognitive complexity helps you understand how different people make sense of that reality and praxis complexity helps you decide which parts of ontological and cognitive complexities ought to be inside and outside of your focus.

One of the most important decisions in any research project is deciding the boundary between focus and scope, and then having made that choice, working out what your scope entails. Depending on the respective stage of a project,, scope can either be largely ignored or, conversely, during other points in the research journey, it can threaten to overshadow the focus so much that the scope effectively becomes the focus. Although ignoring the scope might make your research more achievable, it risks the research being largely irrelevant because it is disconnected from its technical, social and political context. The potential dissonance between the focus and scope of your research can place such a huge burden on your project that, while it might be very relevant to the real world, it risks being unachievable. This tension between scope and focus is especially applicable to PhD researchers who often have to navigate the academic demand for narrow focus and funders’ and society’s demands for relevance, and thus for a potentially larger scope.

How do you decide where the boundary between the focus and the scope of your research should be? How can you identify the potential scope of your work and then take well-informed decisions about a focus that is both relevant and achievable?

The systems thinking field has long acknowledged this tension between focus and scope. How it addresses it can be illustrated by the diagram below (Diagram 1).

Diagram 1: Distinguishing between Scope and Focus in Research

The above diagram displays a triangular graphic that shows how the three elements of a systemic inquiry — understanding inter-relationships, engaging with multiple perspectives and reflecting on boundary choices — are all mutually interconnected. Two of those elements essentially determine the scope of a particular piece of work and the third determines the focus. There is a boundary where the key choices and compromises between focus and scope lie.

Let’s unpick this diagram in detail…

The first task of a systemic inquiry is to identify the scope of the work — in particular the substantial network of inter-relationships — and the nature of those inter-relationships. This is sometimes called understanding the ontological complexity of a situation.. In other words, what is the reality you are dealing with?

However, different stakeholders in your research area will interpret that reality in different ways, based on their histories, cultures, world views, age, specialisation or experiences. As a researcher, you will ‘see’ this complex reality in different ways to your funder, while a person who is participating in or providing data for your research, even your supervisor, will see a different reality. In any given situation, there will be thousands of different perceptions of those realities. There will, therefore, be many different responses to the question ‘what is this research about?’, and many different assessments about whether your research is the right thing to do. Furthermore, those different realities will influence how people behave within and respond to your research. Thus, a systemic inquiry will also need to explore these multiple perspectives to completely understand the situation that is being researched. This is sometimes called cognitive complexity In other words, how do people interpret the same reality?

That combination of two complexities comprises the scope of a piece of research. It includes not only what is ‘out there’, but what people’s ideas are of what is ‘out there’. Taking all of that ‘scope’ into the ‘focus’ of your research is clearly impossible. In order to do the research, there has to be a process of deciding what to include and what to exclude from the scope, so that the focus of that work is practical while also being sufficiently relevant to be achievable and legitimate. In the systems thinking field, this is called boundary setting, and the reflection necessary to decide an appropriate boundary is called boundary critique.

There is, however, one more level of complexity. As suggested by the arrows in the diagram, each of the three elements affects the others. Prioritising a particular perspective not only will affect subsequent boundary choices, but will also affect those aspects of ‘reality’ that will be necessary to understand to do your research. A decision that there are certain aspects of reality that are unmeasurable or unobservable will affect the boundary choices of what resources (people, money, skills, knowledge, things) are necessary to do your research. And those decisions may, in turn, have an impact on which perspectives on the research are prioritised and which are marginalised. A label for this could be ‘praxis complexity’. In other words, the complexity of deciding what is feasible and desirable to do?

There are several implications for you as a researcher. For instance, it implies that your research design is not something that is done at the beginning but rather throughout the entire research program. Every time you discover more about reality, then all perspectives on that reality change, and that in turn poses questions about the nature of your current boundary choices. It also invites questions about how your research can claim that it is the right research to do. There are ethical questions of who ought to make that decision. You? Your supervisor? Your funder? Those positively, or negatively, affected by your research? Those who feel their perspectives have been marginalised may pose a risk to the feasibility, sustainability and legitimacy of your research.

These are difficult issues and the systems thinking field contains many approaches by which they can be addressed. Systems thinking can effectively assist the researcher in their navigation of the complexities between scope, focus and boundary setting. It can also enable them to confidently manage a very wide array of complex strategic questions upon which the success of a research project can depend. Future articles will explore how the systems field addresses them.

This article discusses topics covered during ADVANCE CRT’s Summer School on Systems Thinking at Maynooth University in June 2022. See here for the first article. It can be read as a discourse around designing research, and you are invited to consider how the questions posed offer an inflection point for your research.

This article was first published by the ALL Institute and has emanated from research supported in part by a Grant from Science Foundation Ireland under Grant number 18/CRT/6222. The opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Science Foundation Ireland.

From first-order to second-order evaluation practice: time to shift the ground

The title of the 14th European Evaluation Society’s Biennial conference in Copenhagen in June 2022 posited that evaluation finds itself at a watershed and called for “actions and shifting paradigms in challenging times”.an O'Donnell

Barbara Schmidt-Abbey (Open University)

Joan O’Donnell (Maynooth University)

Kirsten Bording Collins (Adaptive Purpose)

The title of the 14th European Evaluation Society’s Biennial conference in Copenhagen in June 2022 posited that evaluation finds itself at a watershed and called for “actions and shifting paradigms in challenging times”.

At the time of the conference, and when you read this, nobody can be left in any doubt that we indeed live in challenging and uncertain times that require an urgent shift in our thinking and doing as evaluators. The ongoing pandemic, war raging on the European continent, a looming energy and food crisis amidst rampant inflation, and extreme weather events are stark signs of ‘systems failures’ that are becoming increasingly harder to ignore and stay complacent about.

Photo of (L-R) Kirsten Bording Collins, Barbara Schmidt-Abbey and Joan O’Donnell

They hammer home that we are indeed living in a much cited ‘VUCA’ world (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex and Ambiguous). The issues evaluation and evaluators are faced with are often characterised as ‘wicked problems’ (Rittel and Webber, 1973), or even worse, as ‘super-wicked problems’ (as referred to in Hans Bruyninckx’s keynote speech at the conference). Instead of simple, solvable problems, we are dealing with ‘messes’ (Ackoff, 1974). The traditional methods and tools that worked well in ‘normal times’ are being exposed as woefully inadequate.

Contributions at the previous EES conference in 2018 in Thessaloniki, such as Thomas Schwandt calling for ‘post-normal evaluation’ (Schwandt, 2019), are even more urgent now: we truly find ourselves at a watershed, where it becomes more and more obvious that traditional evaluation methods, approaches, institutional arrangements and mindsets are no longer sufficient to meet the nature, urgency and scale of the challenges, and that ‘business as usual’ in evaluation is no longer an option. It may even be part of the problem as was suggested throughout several conversations at the conference.

How then can we as evaluators rise to this challenge, and bring about the proclaimed needed ‘actions’, and ‘shifting paradigms?’

The fields of systems thinking in practice, and of second-order cybernetics can provide us with some useful concepts that can help.

The shifts we need to see are interdependent

The conference themes suggest four interdependent necessary shifts to bring about this change: institutional, methodological, identity and content shifts (see Fig. 1).

These can be arranged as a proposed ‘theory of change’[1], which we use to structure this contribution:

Identity shifts: it is first and foremost necessary for evaluators to transform from within, by turning our attention to ourselves as evaluators, and the roles we play in evaluating. The other necessary shifts are facilitated by this introspection.

Institutional shifts: the institutional arrangements within which evaluations are situated, commissioned, conducted and used must be transformed

Methodological shifts: transforming methodologies, and how they are used

Content shift: the above shifts contribute collectively to a ‘content shift’, where situations are being transformed by evaluation, and evaluation itself is also transformed, at another level.

The need to make second-order shifts

As practitioners, we can easily be overwhelmed by the magnitude of the challenges we face. We may ask ourselves, “how can we possibly manage to tackle all these shifts, when the stakes are high, and action and change are urgent?” To overcome a potential feeling of dread and paralysis, we propose taking inspiration from the fields of systems practice and cybernetics by taking a ‘second-order’ approach.

The most useful shift we can make is to see ourselves as vested stakeholders in the evaluation, with power and agency. For example, this includes questioning framings for Terms of Reference (second-order identity shift) rather than fulfilling contracts using evaluation ‘tools of the trade’ instrumentally and acting like a tradesperson (first-order thinking). The shift can be understood as the difference between doing something unreflectively, routinely, and doing something with a higher order purpose in mind. A second-order approach involves critically engaging in a dialogue with commissioners at the initiation stage about the Terms of Reference, in order to ensure that the purpose of the evaluation is exposed and questioned, and with view to creating favourable conditions of systemically desirable changes to the situation within which the evaluation takes place. ‘Being’ an evaluator in this mode involves ethics: acknowledging wider consequences of the work done (evaluator as craft artisan/bricoleur).

Failure to reflect on our own part in evaluations can too often result in carving up kittens and not just cake, without intention to do harm. While evaluating the success of a cake invariably involves cutting it up and eating it, we sometimes do this inadvertently in complex systems also. It is time to let go of dissecting living systems in the hunt for impacts that can be elusive, and instead shift attention to ensuring that projects are creating the right conditions for change.

Identity shifts: What do we do when we do what we do?

As we can see, if we want to successfully contribute to the desired shifts, it is first and foremost necessary for us as evaluators to transform ourselves from within.

As proposed in the theory of change (Fig. 1), we suggest that it is fundamental to turn our attention to ourselves as evaluators, and the roles we play in evaluating. Change must start with us ourselves. This also requires that we begin to see ourselves as part of the system we are evaluating.

Evaluator inclusion as part of the system is an essential and necessary precondition for such an identity shift. In a recent award-winning paper, Cathy Sharp (2022) suggests that the time for this approach has arrived.

This idea is taken up in Barbara’s Think Tank session “Being evaluation practitioners in a volatile and uncertain world: What do we do when we do what we do?” which is part of her ongoing doctoral research, and builds on some key ideas expressed in Schmidt-Abbey et al. (2020).

The title cites a phrase coined by Humberto Maturana, who invites us to critically reflect about our practice in asking “What we do when we do what we do”? (Ison, 2017:5). This is essentially a second-order question. When speaking about ‘evaluation practice’, the focus is therefore on the practitioner.

The different interactions we juggle when doing evaluations systemically can be brought to life using a playful heuristic of an evaluator as a juggler, simultaneously juggling four balls: the B ball (Being a practitioner), the C ball (Contextualising evaluation to situations), the E ball (Engaging in specific situations when conducting the practice of evaluating) and the M ball (Managing an overall evaluative performance including relationships with stakeholders).

Think Tank participants jointly explored three questions, which may be added to Sharp’s (2022) provocative questions:

How do evaluation practitioners engage with complex situations of change and uncertainty?

How do evaluators reflect on the choices and use of approaches and methods in these situations?

What opportunities exist for evaluators to make a ‘second-order practice shift’ in such situations?

Methodological shifts

Methodological approaches to evaluation need to shift from sustaining business as usual (first- order) to encouraging innovation and continuous viability in the context of rapid and continuous change. Systems thinking has many tools that can support this.

Two tools worth noting are the Viable Systems Model (Stafford Beer 1979) — which establishes the conditions necessary for a programme to sustain viability over time (see fig 3), and Critical Systems Heuristics (Ulrich and Reynolds 2020) which explores the boundaries around a programme and questions the gap between how things are and how they should be. Both are therefore concerned with both evaluating the current state of affairs and designing better alternatives. While VSM emphasises the importance of sporadic monitoring processes, CSH asks questions relating to values and ethics — key considerations for any evaluation activity.

In her conference presentation “Evaluating the enacted transformation of Irish disability services from face-to-face to virtual services using the Viable Systems Model”, Joan proposed VSM as a way of getting to the heart of processes that support developing practices that help us in ‘learning our way out’ of those moments when expertise, habit and competence fail us amidst the complexity and uncertainty we are faced with (Raelin 2007: 500 in Gearty & Marshall 2021). Not only can VSM assess the value that a system offers the environment, it stress-tests the interrelationships between different parts of the system, challenging siloed thinking, lack of coordination either internally or between projects as well as the deployment of resources and governance. These are all essential components of a second-order evaluation.

Picture 3: Image from Joan’s Conference paper: Evaluating the enacted transformation of Irish Disability Services from Face-to-Face to Virtual Services using the Viable Systems Model (Photo credit: Mark König onUnsplash)

Contents shifts

Content changes also require a focus on making sense of complexity in real time and learning forward to guide future action relevant to the future we are creating. It was also the focus of Joan’s workshop on her doctoral research “Shifting Ground: psychological safety as a systemically desirable way to evaluate the development of resilient inclusive and equitable communities”, which explored the enacted response of disability service teams that developed virtual services during the pandemic. Her findings suggest that the degree to which they were able to be fully present and engaged contributed to a felt sense of psychological safety and supported personal experiences of meaning-making at a particularly stressful time for both staff and people with disabilities. Her presentation suggested psychological safety, if reframed as a systemic construct, becomes a core condition for creating resilient inclusive communities, and thus offers a valid focus for evaluation.

This is in contrast to a more first order framing of psychological safety as a way in which leaders think and act to create candor in teams in the interests of innovation and productivity (Edmondson 2019). It can therefore serve as an example for a content shift brought about by taking a systemic and second-order, rather than a systematic traditional first-order research and evaluation approach.

Institutional shifts

An institutional shift concerns the transformation of the arrangements, structures and norms within which evaluations are situated, commissioned, conducted and used.

Amongst others, Martin Reynolds’s presentations reviewed earlier work (Reynolds, 2015) by identifying new opportunities to ‘break the iron triangle’ in which evaluation can be trapped, by shifting to a more ‘benign evaluation-adaptive complex’ in institutional arrangements, to enable more purposeful evaluations, and suggesting value for ‘mainstreaming evaluation as public work’.

Another angle to institutional shifts was explored in the Think Tank “Mainstreaming System-based Approaches in Evaluation: What is our Role as Evaluators?” led by Kirsten, which explored the question of what the role of evaluators might be in ‘mainstreaming’. The idea of ‘mainstreaming’ systems-based approaches can be seen as a way to institutionalise the desired transformation of evaluation, in the way evaluations are done.

This Think Tank intended to share experiences and generate discussion on how we can better integrate systems-based approaches in evaluation. It began with a grounding to come to a common understanding of what we mean by ‘systems-based’ approaches, for which the following characteristics were proposed:

Picture 4: Image from Kirsten’s Think Tank: some characteristics of systems-based approaches in evaluation

Although there are advances to incorporate systems-based approaches in evaluation, including important efforts such as Developmental Evaluation and others, we would argue it is still at the fringes and is not mainstream in evaluation.

The general consensus among participants in this Think Tank was that we have a long way to go, and much education, advocacy and capacity-building is needed to integrate and mainstream system-based approaches in evaluation. We have to start with a ‘mind shift’, and we need to embed systemic approaches in the design and planning of evaluations. It appears that some progress is happening in this regard on the ground, for example, where cross-organisational teams are embedded across processes instead of evaluation offices in large organisations, even if this is still only largely taking place at the programme level, and not organisation-wide.

What could be done to better integrate and mainstream systems-based approaches and what could our role as evaluation practitioners be in this process? Many ideas and suggestions were offered in a lively brainstorming exchange. Some of these included making a clear business case for the use of systems approaches, clearly spelling out the What, Why and How, and using language that resonates with the appropriate audiences. The role of evaluation managers is also seen as critical vis–a-vis commissioning and acting responsibly and ethically. Evaluators need to reinvent themselves, and evaluation needs to become embedded within projects and programmes.

The consensus was that we cannot do this alone and need instead to join forces towards mainstreaming systems approaches in evaluation, in order to prompt the necessary institutional shifts.

Towards institutionalising systems approaches in evaluation practice — where to next?

In order to progress the institutionalisation of systems thinking in evaluation practice, the idea emerged in Kirsten’s Think Tank to establish a new Thematic Working Group (TWG) within EES on ‘evaluation and systems thinking’, to convene a more systematic as well as systemic space for evaluators / members of EES interested in mainstreaming systems thinking into evaluation practices.

Therefore, we plan to develop a proposal to be brought to the Board of EES that is being drafted by a group of volunteers arising from the workshop. A dedicated TWG devoted to systems approaches in evaluation could contribute towards bringing fragmented efforts together, be a forum for exchanges and developments, and share inspiring examples of practice leading to mainstreaming and institutionalising systems approaches in evaluation practice.

It is time to shift the ground. Join us!

Contact any of us!

If you want to know more about the planned TWG and would like to contribute, please contact Kirsten at kbcollins@adaptivepurpose.org.

In parallel, the presented doctoral research continues further. For more information, please contact:

Barbara at barbara.schmidt-abbey@open.ac.uk– if you are an evaluation practitioner dealing with situations of complexity and uncertainty, you can still contribute to Barbara’s research with an in-depth interview, and watch the space for forthcoming results.

Joan at Joan.odonnell.2020@mumail.ie. — for further information on methodological approaches and psychological safety. Joan’s contribution has emanated from research supported in part by a Grant from Science Foundation Ireland under Grant number 18/CRT/6222.

This article was first published 30 August 2022 by the European Evaluation Society: https://europeanevaluation.org/2022/08/30/from-first-order-to-second-order-evaluation-practice-time-to-shift-the-ground/.

References

Ackoff, R. (1974) Redesigning the future. New York, Wiley

Beer, S. (1979) The Heart of the Enterprise. New York, Wiley

Bruyninckx, H. (2022) Keynote speech at EES 2022, 8 June 2022

Edmondson, A. (1999) Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative science quarterly, 44(2): 350–383

Edmondson, A. (2019) The Fearless Organisation. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons

Gearty, M. R., & Marshall, J. (2021) Living Life as Inquiry — a systemic practice for change agents. Systemic Practice and Action Research, 34(4): 441–462

Ison, R. (2017) Systems Practice: how to act — in situations of uncertainty and complexity in a climate-change world. 2nd ed. London, Springer

Rittel, H. and Webber, M (1973) Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sci (4): 155–169

Reynolds, M (2015) (Breaking) The iron triangle of evaluation. IDS Bulletin 46: 71–86

Schmidt-Abbey, B., Reynolds, M., Ison, R. (2020) Towards systemic evaluation in turbulent times — Second-order practice shift. Evaluation, 26(2): 205–226

Schwandt, T. (2019) Post-normal evaluation?, Evaluation, 25(3): 317–329

Sharp, Cathy (2022) Be a participant, not a spectator — new territories for evaluation. The Evaluator (Spring 2022): 6–9

Ulrich, W., Reynolds, M. (2020) in M Reynolds, S. Howell (eds), Systems approaches to making change: A practical guide, Springer, London.

A feast of new ideas: Systems Thinking in research

Joan O’Donnell & Bob Williams

This blog is the first of a series of blogpost contributions outlining basic Systems Thinking concepts presented at the ADVANCE CRT Summer School that Joan and Bob helped to design in June 2022, held in Maynooth University Ireland.

Group Photo of ADVANCE CRT Summer School students, supervisors and trainers

‘The Systems Thinking summer school opened up little doors in my mind to paths that had been unexplored previously. It’s like an added tool to my repertoire and if I get back into old ways of thinking and get stuck, I remind myself of that door. It makes exploring topics more exciting also because it’s more of an adventure with this way of thinking’. Ashley Sheil, PhD Scholar, Maynooth University

The ADVANCE CRT Summer School focusing on Systems Thinking marked the largest and most ambitious event of the Science Foundation of Ireland PhD programme to date. It brought over 60 students and supervisors together for four days in a memorable event that was as much a celebration of being together in physical space as an opportunity to delve deeply into the richness that Systems Thinking offers research.

This introductory blog gives an overview of Systems Thinking and a sense of its importance for transdisciplinary research. It also outlines some of the topics that students experienced during that week.

Overview of Systems Thinking

Systems Thinking is a transdisciplinary field with many influences including biology, mathematics, physiology, economics, philosophy, psychology, sociology, management studies, family therapy, engineering and computing. In simple terms, the systems field provides tools that describe, understand and address ‘complex’ — sometimes called ‘wicked’ — problems.

Its modern-day origins are closely linked to Alexander Bogdanov who published Tektology over a hundred years ago, the biologist Ludvig vonBertalanffy and Norbert Wiener who introduced the word ‘cybernetics’ (steermanship in Latin), and ‘feedback mechanisms’. Systems approaches were used extensively during the Second World War and developed substantially during the 1950s and 1960s; influencing practices as diverse as family therapy, organisational development and engineering. However, that is not to say that it is new: a systems worldview can be traced back as far as the earliest school of Ancient Greek philosophy from the 6th century BC and Taoism from the 4th century BC, both of which sought harmony between the natural and human worlds.

However, the Cartesian worldview that took hold in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries forwarded the notion of the world as a machine, with the result that the scientific method, as it evolved since the 18th century, favoured the study of parts of the machine as ends in themselves. It broke things down into their individual components, analysed them in ways that ignored the stance of the observer (aka ‘objectivity’), and then assumed that the ‘whole’ could be understood by reassembling the parts. In contrast, Systems Thinking offers an antidote to complement this positivist scientific method by focusing more on understanding the relationship between the parts, and different people’s views of those parts, as a means of addressing complex issues.

The summer school explored ways to bring this kind of inquiry to life in their own research projects; but first, a few overarching words on how Systems Thinking supports research:

Relevance of Systems Thinking to research

Systems Thinking supports you to reframe your research situation and recognise your role in co-creating research with those affected by it. Firstly, it helps you navigate the complexity associated with taking a meta-view of a research project and to contextualise issues. You reframe your research as ‘wicked’ problems that that can contribute to improving situations rather than as ‘problems’ to be ‘fixed’. Secondly, it moves away from viewing problems as ‘things’; i.e. the ‘health system’ or the ‘IT system’, and instead perceives them more as human constructs that can be used as tools to explore how people understand reality. Finally, the constructionist foundation ask us to place ourselves as actors inside the research. You are part of the system you are exploring and not as supposedly objective outsiders. That new position implies you need to take responsibility to reflect on how you influence research outcomes, but also the what the broader practical, cultural and ethical consequences of your research are.

Summer School as an enacted process

Consequently, we (Bob and Joan) were tasked with the job of enabling students to think systemically about how their research fits into the real world and how the real world fits into their research. Our emphasis was not only about Systems Thinking but systemic practice. We dived right into working in cross-disciplinary groups and devised a rich understanding of systems concepts using a case study. This involved practising how to explore systemic interrelationships, multiple perspectives and critical boundary decisions. Boundary decisions are important systemically because, contrary to popular ideas, Systems Thinking is not about including everything, but instead being very systemic about what needs to be left out so that we can actually do something.(See diagram 1). The methods we used do this will be covered in follow-up blogs. For now, here is a flavour of the topics we covered during the week.

A rich variety of masterclasses were offered over the following two days:

Evidencing in Research: Dr Martin Reynolds, Senior Lecturer in Systems Thinking: STEM Engineering and Innovation at the Open University, led a session designed to develop students’ systems literacy. This entailed an exploration into how ‘facts’ never speak for themselves, which necessitates making systemically-informed reasoned cases for supporting and/or questioning interventions.

Patterns of Strategy & Eco System Modelling: Patrick Hoverstadt and Lucy Ho from Fractal Consulting introduced us to a unique approach to harnessing systemic forces acting both in organisational and meta systems. By focusing on the relationships between organisations, researchers can better understand how to tap into them to make them work for our research.

Critical Systems Heuristics (CSH) for supporting research: CSH provides a powerful tool for getting to grips with the practice, politics and ethics of making those boundary decisions. This session, led by Martin Reynolds, focused on how CSH can help surface these issues associated with, and arising from research practice.

Systems Principles

The laws and principles upon which Systems Thinking was founded as a discipline provide insight on how, when and why systems remain stable and change at the same time. These principles also support an understanding of what happens when they collapse into new forms or disintegrate. Lucy and Patrick led this session where we took a handful of principles and applied them to a given situation to harvest insights that support the endeavour of doing research in real-world contexts.

Co-inquiry using Soft Systems Methodology (SSM)

The final day was led by Professor Ray Ison, also from the Open University and President of the International Federation for Systems Research. He brought us through a systemic co-inquiry asking “what do you do when you do what you do? i.e. claim to do research? Or supervise research?”. By mapping the responses to these questions, we explored not just our own theories of how things change, but the implications for taking ethical responsibility of our epistemological commitments. We were invited to develop our systems literacy, and develop our Systems Thinking-in-practice capability using some basic concepts from Soft Systems Methodology.

It is impossible to convey the energy and commitment that trainers and students brought to co-creating a rich learning experience, that engaged head, heart and gut in the business of recovering a systemic sensibility to our research practice. We were joined by a cadre of very engaged supervisors that made the experience feel like a unique collaboration between peers. In the background, as there always is in any successful event, was the phenomenal team of Luis Gómez de Membrillera and James Duggan from ADVANCE, who did everything in their power to ensure that everything ran smoothly. Which it did!

Participants experienced eureka moments and world-altering realisations about how to approach research topics across a broad spectrum of disciplines from psychology to mathematics, to engineering. The success of the event is conveyed in the following student accounts:

‘Among other excellent opportunities, the summer program gave me the chance to stand back and create a bigger picture that encompasses my study topic. By doing this, I felt more assured and able to carry on my study more consciously. Furthermore, I had the opportunity to learn about extremely practical System Thinking strategies like the rich picture, CSH and PQR framing — they are helpful to me in both my studies and daily life. In the end, I developed a stronger belief in cooperation and teamwork’. Ramin Solimani, PhD Student UCC.

‘Systems Thinking gave me the tools to gain a better perspective of my research project. I can see a much broader view of the project while still seeing all of the intricate details. Also, for the first time, I can see the interconnections and all relationships between the different elements, stakeholders etc’. Stephen Sheridan, PhD student, TCD.

ADVANCE CRT Summer School Maynooth 2022

In addition to a beer or three and too many sandwiches, the very act of coming together, creating a system of researchers bound by a common identity and facilitated through a common language was, in truth, Systems Thinking in action. Bob concluded with his top tips for o starting on the systems journey:

Be useful. Use systems ideas when you think they would add something useful to your research

Be committed. Start with an aspect of the systems field that interests you

Be careful. Using systems ideas could change your relationship with key colleagues and stakeholders

Be safe. Seek low risk, medium reward first.

Be creative. Don’t be a purist; adapt, invent, modify but stick to the core principles

Plus … have some fun in the process.

The next blog explores the important issue of drawing the line between the focus of your research and its scope. The focus makes it doable; the scope makes it relevant. Think about that.

This article was first published by the ALL Institute and has emanated from research supported in part by a Grant from Science Foundation Ireland under Grant number 18/CRT/6222. The opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Science Foundation Ireland.

Growing Our 21st Century Collective Leadership Skills

What do we do when we do not know what to do next, but are under pressure to do something? Too often something becomes anything, and anything is something that we have done before.

What do we do when we do not know what to do next, but are under pressure to do something? Too often something becomes anything, and anything is something that we have done before.

Credit to: Photo by Lena Khrupina from Pexels

The pandemic prompted speedy innovation and improvisation: it showed us what we could do under difficult circumstances, and gave many people agency to take action that cut across the usual red tape and hierarchical ways of doing things. The extent to which people took positive social action unconditionally in their communities gives some sense of how we can take meaningful action in the face of deep uncertainty, and how we can do so together.[1] And while we are at our most innovative at the early stages of change, before routine sets in,[2] as we move into the post-Covid recovery period, it can be tempting to seek the solid ground of certainty and business as usual. It is as if an inner pendulum swings between wanting the high dry ground of certainty and wanting to step out into the swamp of uncertainty and engage with real issues on the ground. One approach works with numbers and structures; the other with patterns, and the quality of the interrelationships between different elements of the whole. One calls on our individual tenacity to take action, even if it means ‘doing the wrong thing righter’[3], and the other calls on us to slow down, make space and feel our way forward together.

Traditional management tools do not work well with complex problems. They box and simplify, silo them into constituent parts, and managing them with discrete programmes, which are often unwittingly pitched against each other.[4] Social issues are messy, they cannot easily be tucked into the neat boxes of time-bound projects that must produce quantifiable impacts in line with budgetary cycles.

Focusing on Covid recovery is a delicate time to pick up the threads of the last two years and move forward. At a time when we most feel like running for high ground, we need to step into the swamp of the unknown and grow our capability to take collective action and learn forward together amidst an acknowledgement of the complexity of governing in the 21st century.

Too often change initiatives take the form of shifting the furniture around the room, and while structural changes might be needed to get the door fixed, they rarely get to ask the more interesting questions: who is using this space and for what? What ought it be used for? Who needs to be here and is excluded? Why do we need it? What are the unintended consequences of doing things this way?

These are questions we cannot answer alone.

It requires that we lean into a deep sense of our interconnectedness and interdependency, dig deep and connect with each other. The act of turning up and allowing others to ‘arise as legitimate others[5]’ before us and transcend the entanglements that come with job roles and personality in unknown territory is key to unlocking the power of collective leadership.

The task of turning up with such openness chimes strongly with the UN Inner Development Goals across the domains of being, thinking, relating, collaborating and acting. If the Sustainable Development Goals are a blueprint to achieve a better and more sustainable future for all, then the Inner Development Goals give us a clear sense of the kind of inner work all leaders need to engage in.

Being includes a greater sense of embodied authenticity, self-awareness and presence, and developing the mindset of curiosity, willingness to be vulnerable, embrace change and grow. The thinking skills regarded as critical for the future include critical thinking, the capacity to work with complexity and systemic causality and an ability to see patterns, structure the unknown and consciously create stories with a long term orientation. An appreciation for others and the sense of being connected to community is combined with a call for humility that extends to the needs of a situation over self-importance and relating to others with compassion and address suffering. Collaborating requires the skill to really listen to others and foster dialogue, co-creation skills and an ability to embrace diversity, sustain trusting relationships and mobilise others to work towards shared purpose. Together these competencies inspire action infused with courage, optimism and agency to break down old patterns, generate new ideas and act with persistence in the face of uncertainty.

The Scottish Government is really well placed to meet this UN challenge: few countries are resourced with a Collective Leadership Strategy and an experienced team to support it. In fact, having collective leadership festivals to draw out attendees collective capabilities through provocative and enticing offers is unprecedented.

Fig 2. Illuminating Leadership Festival Logo

The Collective Leadership for Scotland team convene ‘we-spaces’ across different levels of the system, that acknowledge our interconnectedness, our interdependency and the fact that what is needed cannot be found in a Gantt chart or a causal loop diagram. They do this in line with the Strategy for Collective Leadership for Scotland, which creates a clear context and purpose for the work, and is aligned with the National Outcomes for Scotland. The strategy commits to building capacity for collective leadership within complex systems, through creativity and innovation. It includes working out loud, sharing stories and connecting different parts of the system to itself.

Regardless of the various roles and perhaps conflicting personal and institutional roles you play in the system — tempered radical, activist, muckraker, artist, parent, neighbour, senior public servant or community worker — there is work to be done together. As Geoffrey Vickers, suggests ‘ people without role conflicts would be [people] without roles and [people] without roles would not be [people].[6]’ And the bigger questions that need innovation post-Covid require new thinking that recognises the diversity of roles, and ways of feeling our way forward together.

We are almost a quarter way through the 21st century- the time to step in and illuminate our collective leadership potential is now.

This blog first appeared on the Collective Leadership Scotland website: https://collectiveleadershipscotland.com/2022/02/24/growing-our-21st-century-collective-leadership-skills/.

It has emanated from research supported in part by a Grant from Science Foundation Ireland under Grant number 18/CRT/6222. The opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Science Foundation Ireland.

References:

[1] Kars-Unluoglu, S., Jarvis, C., & Gaggiotti, H. (2022). Unleading during a pandemic: Scrutinising leadership and its impact in a state of exception. Leadership, 174271502110633. doi:10.1177/17427150211063382

[2] Weick, K. E., & Roberts, K. H. (1993). Collective mind in organizations: Heedful interrelating on flight decks. Administrative science quarterly, 357–381.

[3] Ackoff, R.L. (1999) ‘On Passing Through 80’, Systemic practice and action research, 12(4), pp. 425–430. doi:10.1023/A:1022404515140.

[4] OECD (2017), Systems Approaches to Public Sector Challenges: Working with Change, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264279865-en.

[5] Maturana, H. and Bunnell, P. (1999) ‘The Biology of Business: Love Expands Intelligence’, Reflections (Cambridge, Mass.), 1(2), pp. 58–66. doi:10.1162/152417399570179.

[6] Vickers, G. (1973) Making institutions work. London: Associated Business Programmes.

The future of work and disability: learning our way forward

Continuous advances in technology and Assistive Technology (AT) enhance the range of work that people can do outside the office environment, making working-from-home (WFH), hybrid or remote working a realistic option for many workers with disabilities.

Continuous advances in technology and Assistive Technology (AT) enhance the range of work that people can do outside the office environment, making working-from-home (WFH), hybrid or remote working a realistic option for many workers with disabilities. It may suit those seeking greater flexibility in their working day, allow for better management of disabling conditions at home or sidestep the need to negotiate public transport.

Disability and work poses a complex issue that persists despite broad recognition of the interrelationship between disability, poverty, education, housing in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD) Article 27, which commits to safeguarding and promoting the right for disabled people to work on par with others. While the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) suggests there is a greater need to engage employers to build a better world of work for persons with disabilities, the ESRI finds that there is also a need to understand the experience of disabled people in work.

Participating in the emerging workplace relies on having the right digital skills, access to Information and communications technology (ICTs), the means to pay for them, and that the technology must be accessible.

But this cannot be taken for granted in a workplace where disabled people are hugely underrepresented and experience economic hardship, including digital poverty as a result, according to the International Labour Organisation (ILO). The employment rate of disabled people across Europe prior to the pandemic stood at 48% and the OCED suggested that employment policies have underperformed. The situation in Ireland is especially concerning: we have the lowest rate of labour market participation of disabled people across Europe at 26%, and Eurofound considers the Irish Comprehensive Employment Strategy for People with Disabilities both unambitious and ineffective.

Employers for Change, an Irish organisation explored the experience of disabled workers and their employers working remotely during the pandemic. They identified three areas requiring concerted action, including the need to meet the need for better connection, reasonable accommodations and continuous learning across all levels of the system, each of which is now considered in turn.

Staying connected and visible

Disabled employees needed to feel confident about raising issues with employers and the message from the pandemic is clear: the level of connection required for open and honest communication cannot be produced via training sessions. Nor should the responsibility be outsourced. Creating positive connections preceeds psychological safety — a work climate which allows employees to speak up and take risks without negative consequences. Employees sought more open space conversations that foster sustainable connections that are qualitatively different from the Zoom Fatigue, or wellbeing sessions which were poorly attended by all employees.

Photo by Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona on Unsplash

Visibility of disabled staff affects promotion prospects as well as recruitment levels something that needs to be addressed if working from home is to prove viable. Even prior to the pandemic, it was difficult to sustain disabled voices in Employee Resource Groups, with the result that disability concerns struggle for parity with other diversity issues such as gender and race.

Reasonable Accommodations

Reasonable accommodation refers to measures employers must take to ensure that the workplace is accessible for disabled staff. Improving digital accessibility does not sidestep the need for accessible buildings, but expands the site of accessibility to include all work environments. This is a major concern for disabled employees who are concerned with addressing core accommodation issues such as access to assistive and accessible technology. There was a sense in which employers did not understand the technology needs of disabled remote workers, either assuming that they would have all the AT they needed at home, or that their internal IT systems were more accessible than they were. The upside was that now people felt more included in meetings than before, voice recognition software and the accessibility of Microsoft Word and Zoom increased as time went on. People adopted a stronger ethic of not talking over each other in meetings and using the chat function for side conversations, which supported disabled workers to feel new levels of inclusion as this research participant suggests:

“I have a hearing loss and I knew I was missing a lot of what was being said at meetings and I did bring it to the management’s attention, and nothing was ever done about it. But since working from home, they’ve provided captioning for me for meetings… it’s the first time since I’m working there that I feel like I know everything that’s going on.”

Continuous Learning

Employers did not feel disability confident: they expressed a need for learning for individual disabled employees, managers, and IT personnel, as well as support developing internal policies. The opportunity to learn across organisations was also key to becoming disability-confident and developing the expertise to support disabled staff to become a vital part of the remote workforce. In the words of one employer:

“We need to create a space for them to succeed without having to say ‘this is an employee with a disability’, but rather saying ‘this is an employee that we need to put supports around’. We need to be really clear, really understanding what are the barriers to success. And as an employer we are responsible to remove those barriers”

The rapidly evolving work environment poses continuous fresh challenges for disability inclusion. This includes digital advances affect how work is structured, as much as concern about the effects that the climate emergency will be most strongly felt by those with disabling conditions living in poverty. Enhancing the digital skills of disabled people and improving access to AT will undoubtedly improve this situation, but learning and human connection also form a key component of the way forward.

You can access The Future of Work and Disability - A Remote Opportunity here.

Original Post published on ALL Blog — IDEAS IN ALL — Joan O’Donnell (2022)

The future of work and disability: learning our way forward:

Ideas In All: A blog on assisting living and learning by the ALL Institute, 18/2/2022. https://www.ideasinall.com/the-future-of-work-and-disability-learning-our-way-forward/#more-1421.

The ultimate potential of self-organising systems

The key to understanding our nature as Systems Beings

The key to understanding our nature as Systems Beings

cenzon-Fc9TtSfjKjE-unsplash

The human brain has a network of nearly 70 billion neurons and the cosmic network of galaxies is thought to have at least 100 billion galaxies. Given the vast difference in scale, what could these two most challenging and complex systems in nature have in common? New research suggests that both are self-organising networks. This finding offers a fresh perspective not just on who we are as human beings, but how we naturally organise as living systems.

Is the universe is one giant brain?

Research by scientists Vazza and Feletti (2020) found evidence that both the universe and the brain operate as self-organising systems using similar principles of network dynamics. This seems incredible not just because of the enormous different scales and processes at play, but also because they are made up of very different parts. Both systems are comprised of complex networks spread out in long filaments linked by nodes. By investigating the structural, morphological, network properties, and memory capacity of both systems the researchers concluded that “similar network configurations can emerge from the interaction of entirely different physical processes, resulting in similar levels of complexity and self-organization, despite the dramatic disparity in spatial scales” (Vazza and Feletti 2020).

The idea that we are by nature complex self-organising beings, situated within a universe which is organised in the same way, should give us all pause for thought. It has profound implications for how we could potentially organise society, our organisations, and our lives. As Fritjof Capra (1996) points out — the hallmark of self-organisation is that when a system is thrown way off balance, new structures and behaviours emerge.

What is self-organising and why it matters so much

Self-organisation is a process whereby order or patterns arise from what at first glance seems to be a disorganised system. While technological systems have been organised by commands issued externally: “…many natural systems become structured by their own internal processes: these are the self-organizing systems, and the emergence of order within them is a complex phenomenon that intrigues scientists from all disciplines” (Yates 1987).

The concept of self-organisation is attributed to Ross Ashby, a psychiatrist interested in how the brain restores health after illness. For Ashby however, change was dependent on the level of variety contained within a given system, which curtailed its evolutionary or creative potential. Later thinkers such as Prigogine, who developed complexity theory, came to understand that when a system is thrown off course, or far from equilibrium (e.g. a pandemic), that this is precisely the point where they either collapse or something new is made possible.

What is key to understand here is that order emerges from what may look unruly or chaotic: there is no blueprint, there is no grand plan, just an ever-flowing emergence. And there is a cost to over-controlling the direction of flow…

What self-organising tells us about how we can govern our institutions better

The rule and norms of societal institutions are often what stops change. They are notoriously conservative and self-serving — the exact opposite of what we are talking about here. Creativity and purpose is sucked dry in governance systems that rely on 10 year strategies, blueprints, targets, outputs, outcomes and impacts. Our collective potential for self-organising debunks the assumption that we humans are too selfish and self-serving to behave in ways that serve a common purpose, and we have bought into a lesser vision of ourselves.

Self-organising systems got a bad name in the social sciences when it was assumed that people will inevitably act out of self-interest to the detriment of the common good. Hardin (1968) wrote about the tragedy of the commons archetype, where people would act in self-interest, thus decreasing everyone’s resources. In other words, we would put short-term gain ahead of long-term sustainability. This view gained far more traction in a neoliberal world and could be said to have become a self-fulfilling prophecy in many of the most publicly observed events of our time. But there are other options. We behave in ways that serve the common good all the time. Elinor Ostrom, political scientist and the first woman to win a Nobel prize in Economics, developed 8 principles for sustainable cooperation which rely on clear boundaries, transparent governance as well as acknowledgment and recognition within the meta-system.

Elinor Ostrom Principles of Self-organisation (Author)

What Self-organising shows us about running organisations

Similarly running organisations as top down hierarchical structures is giving way to other options such as the Viable Systems Model (VSM) and Teal Organisations which chime with the findings about how brain and universe self-organise. Both propose flatter non-hierarchical structures which are not only more adaptive to external conditions (Hoverstadt 2008) but are also more profitable (Laloux 2015) .

Stafford Beer developed VSM in recognition of the fact that organisations needed to be “light on their feet and ready to accommodate themselves to the new situations that would arise faster and faster as time passed” (Beer in Pickering 2004 p499). He used the brain as a model for creating a viable system that relied on both the notion that each part of a viable system both contains and is contained within a viable system. This the concept of recursion — which echos the findings of the current research on the link between the brain and universe. While VSM assumes that someone can intervene and re-engineer the system to work better, others place the people within the system and understand that we are integral parts of the system we seek to change.

Frederic Laloux’s approach to reinventing organisations invites people to bring their whole selves to organisational purpose rather than being straight-jacketed by role. Teal organisations are characterised by self-management, rather than power and control based on title. They emphasise peer relationships where people have high levels of autonomy and are accountable for coordinating with others. Strategy is based on what the world is asking of them and responding accordingly. This makes being part of an organisation or an institution an inevitably ethical enactment of our humanity.

What self-organisation shows us about our systems being

Fritjof Capra suggests that an understanding of how we self-organise can enhance our understanding of ourselves as authentic beings. For Capra, self-organisation occurs where there three conditions are met: diversity, connectivity, and local interaction. In other words, action requires that we engage a system comprising of different elements and authentic action leads to the emergence of something new, rather than an outcome that is preordained by the thinking mind. This is the foundation of our humanity.

“The ideas of self-organization are very important to understand the autonomy, the authenticity and basic humanity of people.” Fritjof Capra

It may seem like a contradiction, but if the brain uses self-organising principles, then it also follows that our bodies cannot just be there just to ferry our brains about on their important business. Our whole being is involved in our organising processes. We do not need to remind ourselves to digest our food or breathe — our organs self-organise. But we also co-regulate our physiological states with each other using not just the brain but the nervous system face and heart (Porges 2017). We are fractal parts of a larger whole: in other words, that we are interconnected beyond our wildest imaginations.

“The essential feature in quantum interconnectedness is that the whole universe is enfolded in everything, and that each thing is enfolded in the whole” David Bohm

We cannot avoid being connected to other people because we are wired for connection. We cannot sidestep the consequences of our actions, because we are our actions. We cannot separate our private selves from our public selves, because we are responsible for what we contribute to the whole. And we cannot hide behind our words, because we live in language. We are at heart autonomous systems beings. In the words of David Bohm: “the essential feature in quantum interconnectedness is that the whole universe is enfolded in everything, and that each thing is enfolded in the whole.” That includes us Systems Beings.

About the Author: I am a doctoral researcher in psychology and lecturer in systems thinking. I am interested in how we learn to live in our bodies whilst engaging with technology. I am an advanced embodiment practitioner, thinking partner, and facilitator, with an interest in finding our way through messy systemic issues using body wisdom. I live with my husband, son, cats, hens, and bees in Dublin, Ireland. I also edit https://medium.com/living-in-systems.